![]()

“Zen and the Art of Design Excellence” (or “Lifestyle Allegiance” – take your pick) could be the byline for the Shaker legacy. This religious sect’s overall philosophy emphasized extreme simplicity, maximum functionality and conservation of natural materials, all of which make the style just as relevant today as it was during its peak in the mid-19th Century. From their humble origins from across The Pond to their sustained popularity today, we’ll investigate how the Shakers were just a little bit Country, a little bit Rock ‘n Roll, and quite a bit New Age.

Tell Me A Story

Evaluating them with our modern perspective, the Shakers were simultaneously a group of extreme traditionalists and daring innovators. First led by “Mother Ann” Lee in Manchester, England, as an offshoot of the Quakers in the mid-1700s, they worshipped – in their signature quivering, rave-like ecstatic way – under the cumbersome name The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. (Now you understand why we just call them Shakers.)

The Anglican English didn’t particularly support the idea of Ann Lee as the symbol of the second coming, so Mother packed up her small group of followers and headed where many religious pilgrims dared to go: New England, otherwise considered The New World. It was in this wide-open land that the Shakers really got their groove on – er, uh… realized their freedom – and lived by their codes:

– a little bit Country

- “it takes a village” – communal lifestyle

- “I need a cold shower” – abstinence

- “tell it to dear old dad” – confessions of sin

- “by the letter” – lots of rules

– a little bit Rock ‘n Roll

- “I have a dream” – equality of race

- “I can do anything you can do” – equality of the sexes

- “make love, not war; OK, just don’t make war” – pacifism

– quite a bit New Age / Progressive

- “God is in the details” – creating a working Heaven on Earth

- “less is more” – beauty found in simplicity

They were so concerned with codes, in fact, that in 1821 they drew up (and continued to revise throughout the rest of the century) specific rules by which to live, work, and worship. These orders were knows as Millennial Laws, and they were established at their home base in Mount Lebanon, New York.

They were so concerned with codes, in fact, that in 1821 they drew up (and continued to revise throughout the rest of the century) specific rules by which to live, work, and worship. These orders were knows as Millennial Laws, and they were established at their home base in Mount Lebanon, New York.

The Laws even went so far as to dictate building methods – site plans, space plans, construction techniques and materials – all of which were scrupulously followed by all Shaker Villages. To give you an idea, one law stated: “Odd or fanciful styles of architecture may not be used among Believers.” Not exactly a spec, but a guideline nevertheless.

By the way, several of these villages can be visited today. Preservationists, restorers, craftsmen and those just nostalgic for the Shaker way of life and respectful of their skills continue to fund and care for these concentrated examples of American history and culture:

- Canterbury Shaker Village – Canterbury, New Hampshire

- Hancock Shaker Village – Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village – New Gloucester, Maine

- Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill – Harrodsburg, Kentucky

- Shaker Museum of South Union – Auburn, Kentucky

Down To Copper Tacks

So what characterizes all things Shaker” Some adjectives to get us started are:

- light… in wood tone and construction

- strong… in joinery and form

- austere… in decoration and design

Other descriptors that come to mind are bare, basic, graceful, functional, linear, utilitarian, necessary, elegant, efficient, modest, serene, durable, orderly and clean.

Other descriptors that come to mind are bare, basic, graceful, functional, linear, utilitarian, necessary, elegant, efficient, modest, serene, durable, orderly and clean.

These design characteristics came not from artistic principle, but instead from religious fervor. Shakers truly believed that laboring in of itself was a method of worship – an act of God due to Him being the driving force guiding their design direction. Not only were their forms pure and devoid of superficiality, but their purpose and thoughts were too.

Though historians consider the Shakers to have been at the top of their creative game from 1820 – 1860, they produced many pieces before and since. Before the era, the construction methods were crude as techniques were developed and perfected. After the era, the Shakers “went global” – or as global as you could during that time – by offering their admired and refined pieces to “the World” (i.e. anyone not a Shaker).

Because the villages were self-sustaining, their philosophies on form extended to a vast number of items:

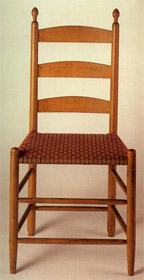

- furniture: chairs (including the world renown “ladderback” that they eventually patented), rocking chairs (including the innovative “ball-and-socket” design, which they also patented), benches, stools, desks, beds, and tables (work, trestle, tripod stands, etc.)

- storage: bookcases, trunks, chests, cupboards, sewing boxes, shelves, peg boards, and bentwood storage boxes

- household goods: baskets, clocks, rugs, dolls, brooms, brushes, and washstands

In keeping with their mission to build with absolute purpose, the Shakers embraced the concept of built-in furniture, which we take for granted today. They designed pieces knowing exactly how and where they would be used, and, equally importantly, they designed them to be used for the long haul. Poor craftsmanship was seen as slighting God and striving for excellence as honoring God. As Mother Ann preached, “Do all your work as though you had a thousand years to live and as you would if you knew you must die tomorrow.” Ah, the good old days.

As you might imagine, the Shakers’ primary building material – whether in architecture or interior items – was wood. Of course they used what was available to them in bountiful New England: maple, oak, birch, cherry, pine, ash, elm, chestnut, sycamore, butternut and various fruitwoods.

As you might imagine, the Shakers’ primary building material – whether in architecture or interior items – was wood. Of course they used what was available to them in bountiful New England: maple, oak, birch, cherry, pine, ash, elm, chestnut, sycamore, butternut and various fruitwoods.

They used hand-formed chisels, lathes and saws to shape the raw wood into both straight and curved slats for furniture arms, legs, stringers and backs, as well as wooden hardware, most commonly found in mushroom-shaped pulls. Legs could be tapered, straight, turned or splayed, and the end product finished with paint or simple oil varnish.

The only “embellishment” was that of exposed dovetail or tongue-and-groove joints and the occasional turned flourish of a finial atop a bedpost or chair. Since seating was exposed frame and consisted of either wood, rush, cane, cotton tape or woven cloth, upholstery didn’t even come into play. Even if it had, the textiles would have been basic in weave and plain in pattern.

The only “embellishment” was that of exposed dovetail or tongue-and-groove joints and the occasional turned flourish of a finial atop a bedpost or chair. Since seating was exposed frame and consisted of either wood, rush, cane, cotton tape or woven cloth, upholstery didn’t even come into play. Even if it had, the textiles would have been basic in weave and plain in pattern.

Original pieces will now cost you a small fortune, but there are many manufacturers producing quality, affordable reproductions. Just know that items handmade in the pure Shaker tradition could be almost as pricey as the lovingly worn originals found during antique shop expeditions; however, pieces merely mass-produced by vendors with a little Shaker flavor usually won’t set you back quite as much.

The focus on function and simplicity is the reason the Shaker style not only manages to survive, but continues to thrive. Similar to the Pennsylvania Dutch, Danish Modern, and Arts and Crafts styles, the back-to-basics quality blends into a full range of interior settings. From traditional to transitional to modern to contemporary, Shaker forms tend to find a comfortable niche. Mother Ann would be proud.

Photographs courtesy of:

Photographs courtesy of:

Mount Lebanon Shaker Village

Shaker Museum and Library

Shaker Workshops

Shaker Ltd.

Are YOU obsessed with an era, a designer / architect or a particular weave of fabric” Then share your little secret with us. We just might feature it or you can write about it yourself. Type quickly and be sure to put OLD SCHOOL in the subject line. contact@plinthandchintz.com