Arkansas is known more for hot springs, Razorback football, and Bill Clinton than for fine art and culture, but with the opening of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, The Natural State’s image is shifting. The brainchild of art lover Alice Walton, one of the wealthiest people in the U.S., the museum is an intersection of art, architecture and nature, which is reportedly what she charged Israeli-born, Boston-based architect Moshe Safdie to create.  Recently we were fortunate enough to receive a personal tour by Trails & Grounds Manager and family friend, Clay Bakker, and we have supplemented this article with photographs contained in our Crystal Bridges Facebook Album. As the 120-acres surrounding the museum is one of the largest native plant gardens, Bakker’s role is significant, and the Arkansas-native was proud to talk about the project’s evolution and outstanding result.

Recently we were fortunate enough to receive a personal tour by Trails & Grounds Manager and family friend, Clay Bakker, and we have supplemented this article with photographs contained in our Crystal Bridges Facebook Album. As the 120-acres surrounding the museum is one of the largest native plant gardens, Bakker’s role is significant, and the Arkansas-native was proud to talk about the project’s evolution and outstanding result.

Location, Location, Location

Bentonville, Arkansas, may seem like an odd place for a first-rate art collection, but Walmart isn’t the only corporate powerhouse that calls the 25th state’s northwest region home. Both J.B. Hunt and Tyson Foods, giants within the shipping and food industries, respectively, have also significantly contributed to the area’s economy, growth and stature.

Even though Bentonville is no longer the small town where the Walmart heiress grew up, Walton has taken great pains to make the museum and its collections accessible to the both the city’s residents and the public at large. Not only is the complex integrated into the urban fabric, connected to the downtown square – home of Sam Walton’s original five and dime – via walking and biking trails, but thanks to a multi-million donation from Walmart, admission for everyone is free.

Building Up

Admittedly the first time we heard the museum’s name, images of cut glass animal figurines and Thomas Kinkade kitsch flooded our minds, but the reality could not be more different. Just to clear things up, the museum’s name comes from the bridge design integrated into the structure’s architecture and the adjacent Crystal Spring that was reformed to feed the site.

Construction brought a series of challenges. Apparently completing the foundation alone took about 3.5 years. Crews cut into solid limestone, uncovering cavern after cave, all of which needed to be stabilized with concrete before construction of the building could commence. And because the plan called for incorporating the existing creek into the overall design, for six years they diverted the water into a tunnel underneath the construction site, only opening the floodgates and filling the ponds at the eleventh hour. In fact, in this wonderful segment by CBS Sunday Morning recorded just days before the museum opened in the autumn of 2011, you can catch a glimpse of the ponds sans water.

As often happens on expensive projects, prior to construction a mock-up was built both to exhibit and to analyze the intricate design of the building’s complex roof assembly. Smartly, the mock-up was saved and incorporated along the Tulip Tree Trail, where it has been fashioned into an open-air shelter to house participants during “Discover the Grounds,” the landscape talk series regularly given by Bakker and others involved with the design and upkeep of the trails and grounds.

Stunning Results

The structure’s exteriors are punctuated with wide planks of western cedar. In order to obtain perfectly smooth surfaces without knots and other blemishes, the planks were taken from the trees’ heartwood, and the precious cargo arrived at the job site individually bubble-wrapped like pieces of fine china. Accompanying the cedar are exquisitely smooth architectural concrete panels that were made one-off on the job site from plastic forms. Together these two materials serve as a pleasing canvas for the shifting reflections off the waters below.

The day we visited, the usually lovely blue-green ponds were a muddy brown because the area had been hit by aggressive thunderstorms the night before. The state change revealed the sizeable level of run-off present on the site, and Bakker confirmed that pond maintenance requires creative solutions. Sediment builds quickly along the bottom of all three ponds, so the staff must clean them out fairly often to maintain the complex’s pristine beauty.

The sweeping roof structures of the two “bridge” wings are held in place by leviathan cables as if they are working suspension bridges. Clad in copper, their vast surface area is developing a soft purple patina that Bakker attributes to the acid levels present in the area’s rain. On their undersides, the assemblies feature ceilings of Arkansas pine, a satisfying juxtaposition to the sophisticated glass curtain walls, contemporary interiors and stunning collections.

Birth Of A Nation

The collections are presented in chronological order starting with “Celebrating the American Spirit,” which features imagery from a young, burgeoning America. Highlights include:

- Hudson River School landscapes – notably “Kindred Spirits” by Asher Brown Durand, a student of the movement’s leader, Thomas Cole

- the portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart that has appeared on the $1 bill and U.S. postage stamps

- oils by Martin Johnson Heade, who depicted detailed, saturated South American flowers, birds, and landscapes

- aquatints by Karl Bodmer, hand-colored lithographs by George Catlin and watercolors by Peter Rindisbacher

Next visitors experience the colonial to early 19th century pieces focusing on subjects like the Civil War, slavery, Western Expansion, and tradesmen (blacksmiths, glass blowers, etc.) at work. The well-known names of John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt show up here, as well as the less familiar George Inness and William Merritt Chase. A personal favorite ended up being a George Henry Smillie watercolor and pencil on paper from 1885 titled “Coastal Scene, “New York.” The seascape’s greeat size, scope, perspective, movement and attention to detail mesmerize by placing the viewer inside the dynamic scene.

From there the focus becomes more intimate and concentrated. Visitors first move through a room devoted to the captivating, sepia-toned photogravure work of Edward Curtis and his experiences with Oklahoma Indian tribes. Following those is a small space dedicated to the legendary folktale of “The Arkansas Traveler” and to memorabilia from the “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” era when the Whig Party’s William Henry Harrison and John Tyler campaigned aggressively against Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren during the 1840 presidential campaign.

Into The Modern Age

The early 20th century collection resides in one of the bridge wings. Not only do the floor to ceiling windows give visitors the feeling of floating upon the water, but they place them among the natural surroundings with its snakes, carp, turtles, crawfish, frogs, and – according to Bakker – a lone mink. Outside amid the flora and fauna is a large metal sculpture by Mark di Suvero that reminds gazers where they are and refocuses attention back inside to the collection waiting before them.

As one might imagine, the wing’s copious fenestration results in an immense amount of sunlight flooding the space. As not to harm the art, Safdie designed inner rooms, for which he has been criticized as inconsistent with the overall design.

Though the “gallery box” solution might not be the most elegant one, it does do the job of protecting the immense collection, which includes:

- imposing female portraiture by James McNeill Whistler and Alfred Henry Maurer

- the iconic “Rosie the Riveter” by Norman Rockwell

- the sharp edges and deep shadowing of Ralston Crawford

- both rural and industrial scenes by Thomas Hart Benton

What follows is the bright Modernist palette and Cubist influence from artists like Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Marsden Hartley, Joseph Stella, and Stuart Davis, founder of the Synchromism Movement. Georgia O’Keefe keeps the men company, and the museum is reportedly in the middle of negotiations either to acquire or share a large O’Keefe collection, so stay tuned.

Pop And Circumstance

Rounding out the museum is an impressive anthology of 20th century art, which feels worlds away from the point where the museum’s artistic, historical journey began. The Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollack, Janet Sobel (who is reported to have inspired Pollack’s signature style), Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, and Adolph Gottlieb resides alongside Pop Art kings Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

Work by icons like Louise Nevelson, Susan Rothenberg, and Josef Albers appear, as does the hyper-reality of Richard Estes, Andrew Wyeth and son Jamie Wyeth. Outside the main gallery in the auxiliary wings hang some rather disturbing, more difficult pieces, which are mainly portraits and self-portraits by the likes of Paul Cadmus, Oscar Bluemner, George Tooker and others.

As visitors move into the contemporary era, they encounter:

- an intricate bronze wire sculpture by Japanese-American sculptor Ruth Asawa

- “Big Red Lens” in cast polyester by Frederick Eversley

- “Soundsuit” by Nick Cave, a fabric sculptor and performance artist

- “Beethoven’s Trumpet (With Ear)” by John Baldessari

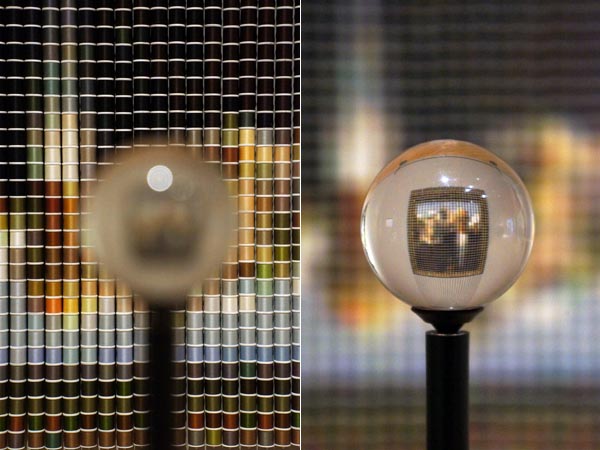

The most fascinating piece “After Grant Wood” by American installation artist Devorah Sperber. She painstakingly assembles spools of thread a la the school of Pointillism to recreate iconic paintings – in this case, Grant Wood‘s “American Gothic” that come into focus when viewed through a prism installed in front of the work.

The Hills Are Alive

The museum’s monumental collection is by no means confined within its walls. The copious outdoor space allows for larger pieces – some site-specific – to live and breathe as intended. Notable pieces include the polished stainless steel tree titled “Yield” by American sculptor American sculptor Roxy Paine, the redwood sculpture “Already Set in Motion” by Robyn Horn, and the mobile stainless steel sculpture by George Rickey titled “One Fixed Four Jointed Biased.”

Aesthetic dessert comes in the form of a creation by James Turell titled “The Way of Color.” This interior light installation, which sits on the scenic hillside of the Art Trail, offers visitors a view of the sky distorted by lighting effects that change with the exterior light and weather conditions. Fortunately, its seats are heated so visitors can comfortably experience this Skyspace even in cooler weather.

More To Explore

Directly adjacent to the museum’s grounds is the Compton Gardens & Conference Center, a 6.5-acre area that has been developed into a woodland garden concentrating on native species. Present far before the museum existed, the gardens are named after Dr. Neil Compton, a well-respected physician and naturalist from Bentonville who studied and experimented with native plants. The proximity of this jewel is the perfect complement to Alice Walton’s labor of love and only makes a visit to Bentonville more appealing.

Lastly, though it has nothing to do with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a quick 20-minute road trip north to Bella Vista Village is worth tacking onto your journey as the stunning Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel sits there nestled into the forest. Designed by renowned architect Faye Jones, an Arkansas native and apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright, the non-denominational chapel is a monument to detail and the perfect place to pause, contemplate and appreciate the wonder and beauty of our world. We have included a few photos here in this Facebook Album. Enjoy and make a plan to visit soon.