![]()

contributed by Sheree Schold [World Design Day 2005 Project Leader / ASID & IIDA Student member]

Touring Scotland is like jumping into a History of Design book — literally. Medieval castles your thing” They’re close no matter where you are. Cathedrals with saintly artifacts help rid you of designer’s block” There are plenty of them. Roman ruins” Uh huh. Buildings and designs by architects you’ve studied” Why of course! Okay, what about cutting-edge contemporary architecture and design in all its controversial glory” Yes indeed. All of this in one small country with a great attitude and people who go out of their way to make sure you find what you are looking for. Century by century, let’s explore both the historical and contemporary finds under the cloudy skies of Scotland.

Sorry Charlie

Short on time, we soaked up all we could around Edinburgh, made a couple of short stops in Glasgow , and spent a day on the opposite coast at Culzean Castle. Apologies to the Mackintosh fans (Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Scottish architect and designer, 1868–1928), but one has to have priorities in this country, and Rennie didn’t make the cut — next trip for sure though.

Twelfth Century: Hurray For Holyrood

Twelfth Century: Hurray For Holyrood

We began our rainy treasure hunt in Edinburgh by climbing up to Edinburgh Castle and visiting the minimalist chapel of St. Margaret, which was built sometime during the reign of King David I of Scotland , 1124–53. On a rock, of rock, it has lasted like rock. Once inside the chapel, the outrageous number of tourists swarming the grounds seemed to vanish and leave us with a quiet, spiritual peacefulness — a sense of time gone by and of future approaching, our itty spot in it all highlighted somehow. Now how does a squat, little old building do that” What calm, Zen-like inspiration in there!

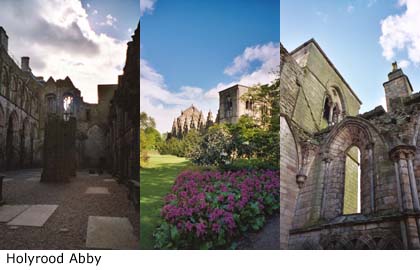

In Edinburgh, the ruins of the Holyrood Abby (1128) and the overpowering darkness of the Gothic Church of St. John, and in Glasgow, the impressive Glasgow Cathedral (built during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and renovated in the fifteenth century, this building survived the Reformation intact), were as inspiring to us as they must have been to their original congregations — classic shapes and forms, nooks and crannies, interesting elements, and fabulous plays of shadow and light.

Seventeenth Century: Natural Progression

Near the Holyrood abbey on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh is the Palace of Holyroodhouse (built during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), which yielded the Portrait Room. We liked the way natural light was used for viewing the dark paintings. Someone really did his homework for that feat!

In the 1670s, Scotland founded its Royal Botanic Garden and we liked its location as a fabulous place to take a break and contemplate a bit of nature’s design and man’s pleasure in it. (The expansive gardens inspired a series of seven Aubusson tapestries that we found later at Hopetoun House that were woven in the 1670s too.)

Eighteenth Century: Hopetoun Springs Eternal

Eighteenth Century: Hopetoun Springs Eternal

A lovely couple had pity on us when we went looking for Hopetoun House (1699–1707). We had gotten off the train and discovered the house was three miles away and no taxis were available! But we had a nice and very informative ride out to the house anyway!

The house was built by Sir William Bruce and is a fine example of early Scottish Georgian Architecture, with a pine-paneled circular stairway, an original cupola painting on plaster, and interesting corner chimney designs. William Adam designed the additions and enlargement of Hopetoun, which were published in Vitruvius Scoticus, and the additions were begun around 1721. Sons John, Robert, and James completed it around 1767. We read a lot about Robert in our studies, but James did most of Hopetoun’s interiors. He was really good, but Robert was better!

The entire Hopetoun House is a treasure find: 1700’s chinoiserie and Vanderbank tapestries done in the “Indian manner” and probably woven by Leonard Chabaneix, a Huguenot weaver from London; Antwerp tapestries; a 1750s and 60s pier-glass and console table, mahogany chairs, and other great furniture designed by James Cullen; a Gilt four-poster bed from Mthias Lock of London; an Isaac Ware chimneypiece; a fabulous Rococo drawing room with plaster work by John Dawson; a marble neoclassical chimneypiece from drawings by Robert Adam;  a great wrought iron stair railing by William Aitkin; a 1820’s Regency-style dining room by architect James Gillespie Graham; examples of Meissen, Minton, Dresden, Derby, and Chinese Canton Celadon; plus, paintings by renowned artists that span many centuries. But it was Adam’s South Pavilion that captured my attention — there was just something about that large open neoclassical-style space, intended as a library and used as a ballroom, which called out to me with all kinds of design possibilities —what would Robert have done with that room to finish it with fine detail”

a great wrought iron stair railing by William Aitkin; a 1820’s Regency-style dining room by architect James Gillespie Graham; examples of Meissen, Minton, Dresden, Derby, and Chinese Canton Celadon; plus, paintings by renowned artists that span many centuries. But it was Adam’s South Pavilion that captured my attention — there was just something about that large open neoclassical-style space, intended as a library and used as a ballroom, which called out to me with all kinds of design possibilities —what would Robert have done with that room to finish it with fine detail”

If you like Georgian Design, you’ll fall in love with the heavy symmetrical architecture of Edinburgh’s New Town. The plan, designed by James Craig in 1766, called for straight streets, squares, and crescents. In fact, this is probably the best and largest example of his work that can be found in one place.

On the opposite coast from Edinburgh we went to Culzean castle (1777–92), a fortified eighteenth century stronghold, which was an incredible treat. It looked so barren, cold, and practically uninhabitable in photos — but oh my goodness! What an appealing place to call home. Robert Adam really scored big on this one and brought many design eras together in one composition! The grounds were wonderful — I didn’t expect to find palm trees, walled gardens, an orangery, walking trails, a hunting lodge, farm buildings and more — all touched by Adam. And the views! No wonder families have fought over that spot since it was first discovered.

Nineteenth Century: Palm-Made

Nineteenth Century: Palm-Made

For a touch of elegant, Victorian-era style, we headed to the iron and glass of the Tropical Palm House (1834) and Temperate Palm House (1858) in the Botanical Gardens. The extremes to which the people of that time would go for keeping all their wonderful plant collections!

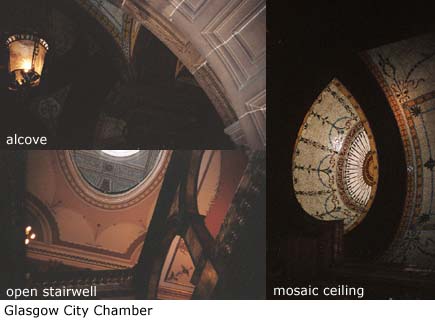

The Glasgow City Chambers (1888) was a wealth of political and industrial history. The classical Italian Renaissance design is true to its inspiration: fabulous inlaid murals, marble, vaulted painted ceilings, you name it — we soaked in the Renaissance!

Twentieth Century: Monkey Business

To take in a little of the early 1900s, and get some nice wool sweaters, we visited Jenner’s department store in Edinburgh — great natural and man-made lighting, open spaces, and tucked-away cozy spots! After taking the original store elevator to the top floor, we discovered contemporary designer furniture and other treasures to comfort us.

For a taste of the 1920s, we ducked into the Drum and Monkey for some delicious fish and chips and to connect with the eminent architect Andrew Balfour. His building, which houses the popular Glasgow hangout, is comparable to classic American architecture of the same period. The interior columns, ceiling design, and strict grid layout of the streets in that part of town are representations of eighteenth and nineteenth century design. We discovered these historical design tidbits on the menu while sipping the local brew!

When we wanted to feel at home and connected to our modern world we headed back to the Sheraton Hotel and the Edinburgh Convention Center complex. Its clean lines and interesting geometry, along with some Starbuck’s coffee — or single malt scotch — soothed our travel-weary bones and prepared us for more great design.

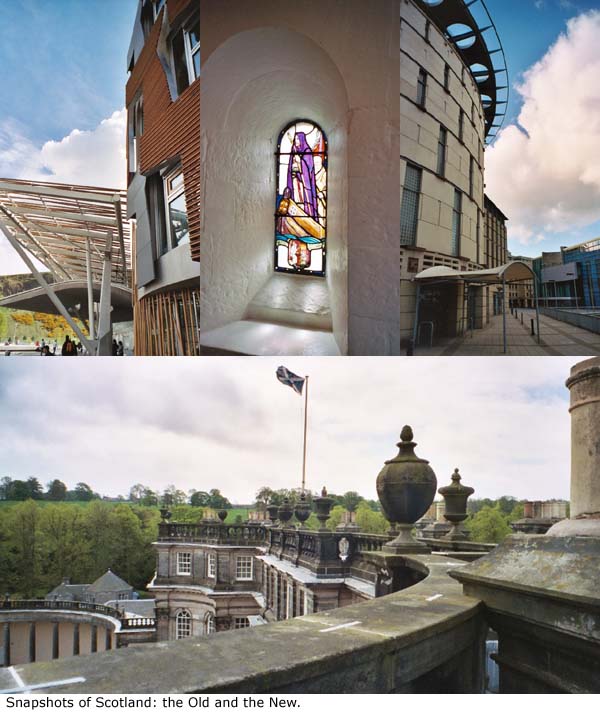

Twenty-First Century: Spanish Spoken Here

The truly contemporary Scottish Parliament Building, by Enric Marilles, topped off our visit as the grand finale. The late Spanish architect’s design for the Holyrood public building delivered everything you would expect from a cutting-edge Catalan architect who had been influenced by an Italian one. Marilles died in 2000, and his Italian architect wife was left to fight the battles of actually bringing the ideas to reality — she did it, and the awards are coming fast and furious.

Great Scot

Whether you like the really old or the future-oriented new, check out www.scottisharchitecture.com — there’s a whole lot more to see! It seemed like those people whose paths we crossed were as eager for us to find their treasures as we were to see them. How could you possibly go wrong in a country where the local eating establishments fill you in on design and architecture while they tell you what they serve for lunch!